The Friday Poem on 16th May 2025

D.A. Prince reviews 'The Wrong Person to Ask' by Marjorie Lotfi (Bloodaxe, 2023)

On seeing Iran in the news, I want to say

my grandmother was called Nasreen,

that she died two years ago in Tabriz

and I couldn’t go to say goodbye,

that she knew nothing of power,

nuclear or otherwise. I want to say

that the bonfires for Chahar Shanbeh Suri

were built by our neighbour’s hands;

as children we were taught to jump over

and not be caught by the flames. I want to say

my cousin Elnaz, the one born after I left,

has a son and two degrees in Chemistry,

and had trouble getting a job. I want to say

that the night we swam towards

the moon hanging over the horizon

of the Caspian Sea, we found ourselves

kneeling on a sandbar we couldn’t see

like a last gift. I want to say

I’m the wrong person to ask.

‘On seeing Iran in the news, I want to say’ is from The Wrong Person to Ask by Marjorie Lotfi (Bloodaxe, 2024) – thanks to Marjorie Lotfi and Bloodaxe Books for letting us include it here

The whole spectrum of knowable and unknowable dangers

A title matters: the book’s first words, and then your immediate – possibly knee-jerk – response. It’s an instinctive assessment. The title appeals or it doesn’t. After all, there are plenty of other books catching your eye. Some writing gurus might suggest an attention-grabbing, eye-catching title, all garish thunder-flash and full sound (you can add your own selection here). However, I can’t recall any advice in favour of a deliberately self-effacing title, almost apologetic, one doing the reverse of calling attention to itself. Yet that is what Marjorie Lotfi has chosen, a title that feels as though it’s backing away, edging towards the door and some way of escape, seeking anonymity. So, why?

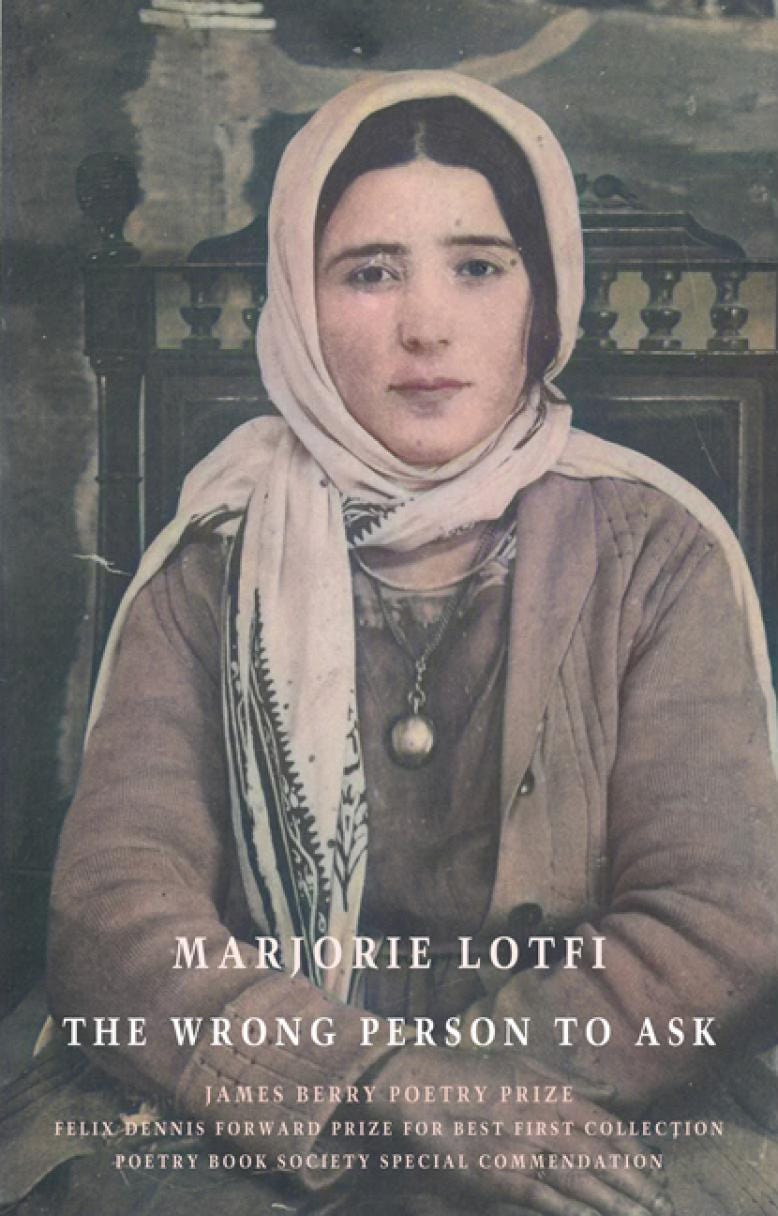

Her own history provides some answers. For this collection some background deepens the reader’s understanding. She was born in the USA and moved to Tehran as a baby with her American mother and Persian father. In 1978 (the Iranian Revolution) she and her mother fled Iran at an hour’s notice, leaving her father behind. She was a child, with a child’s-eye view of what was happening, and a child’s memories of home. She writes these poems as an adult, holding the past and her adult knowledge in fine balance. Through her father’s family she inherited a history of separation: his great-grandmother had been separated from her daughter, Soghra, when the Iran / Azerbaijan border closed in 1917. It’s Soghra’s photograph as a young woman that gazes out from the book’s cover.

Lotfi’s background is from countries that are never out of the news. In 2015 Iran signed the Iran Nuclear Deal, and then withdrew in 2018. Lotfi has written two poems, linked, in response, although you need to look at the notes to understand this context. The first poem, ‘On seeing Iran in the news, I want to say’, focuses on her memories of family:

my grandmother was called Nasreen, that she died two years ago in Tabriz and I couldn’t go to say goodbye, that she knew nothing of power, nuclear or otherwise.

Recalling Iran, Lotfi remembers neighbours, jumping bonfires, swimming in the Caspian Sea. How can she answer questions from American colleagues about Iranian politics and nuclear power? The poem ends: “I want to say / I’m the wrong person to ask.” The ambiguity in ‘want’ intrigues me. Does she utter these words? Or does she say something else – an adult, politically informed answer, perhaps – burying what she would really like to say? When she takes part of this final line to use as the title for the subsequent, linked, poem, ‘The Wrong Person to Ask’, (written in response to withdrawal from the Iran Nuclear Deal), she pleads to be asked about the reality of her memories in five stanzas, all opening ‘Ask …’:

Ask about the cherry tree at the bottom of the garden, and the only time I remember it in fruit: my father smiling, pulling me from the cleft of its branches in darkness. Ask about the bars on my bedroom window. Ask me how many sugar cubes I could slip into my chai before Maman Borzog noticed. (Four.)

Memories pour out, apparently at random; it’s how children remember, and written with a child’s vocabulary as Lotfi accesses her past directly. The poem introduces her grandmother, Maman Borzog, warmly celebrated here and also in ‘Two Grandmothers (Tehran, 1978)’, when the American and Iranian grandmothers meet, with no common language. Maman Bozorg accepts a blonde daughter-in-law, who “doesn’t know / a word of Farsi, or how to taarof, always / refuse first, before accepting a gift.” (‘Maman Bozorg’)

When Lotfi uses a Farsi word she makes its meaning clear via the context, not by notes. It may seem a small – and perhaps irrelevant – detail but it’s not. It’s a way of being inclusive towards the reader while simultaneously mirroring the way Lotfi’s mother learned the social customs.

Notes, however, explain ‘The Game’, the BBC’s online game Syrian Journey: Choose your own escape route, in which the poet pitches the risks and reality of escape against the safety of online make-believe.

There was the game of counting gunshots in a riot, and buying cigarettes for our too-blonde mother; the game of the school set on fire while we were still in it, and watching the clock until the return of my brother.

Quiet reality: no ranting, no anger, just the truth. Bloodaxe has allowed poems to face each other, in dialogue, so that significant details are picked up and expanded, and so that they insist, quietly, on the reality of childhood during revolution. The facing page, ‘Crossing the street for mother’s cigarettes’, shows Lotfi skipping over shrapnel, wondering at “the constitution / of puddles: water, gasoline, blood?” and puzzling where the cars have gone. In another pair of poems – ‘Picture of Girl and Small Boy (Burij, Gaza, 2014)’ and ‘Picture of Boy, Looking Away (Gaza, 2015)’ – Lotfi’s past and the continuing media photographs or children in the wreckage of their homeland come together:

I would like to tell her not to wear such flimsy shoes, that rubble contains the whole spectrum of knowable and unknowable dangers: sheets of metal, ripped to knife edge, live wires, bloated arms reaching for light

She combines an adult’s distance with the intimacy of knowing what the children in the photographs are dealing with. Her past feels very close to the surface, even as she looks at another country, the present century. The first half of the collection – it’s in two separate sections – closes with ‘The End of the Road’, a sequence of eight poems chronicling how an exiled woman’s life inhabits her memories: language, children, returning to a homeland that was, and is no longer, hers. Home – that’s what this collection is about, and what home means:

In her eightieth year, she imagines each sip of tea as home, searing and black in the old way, sugar held on the tongue, sweetening what is to come, what fire in her mouth she has yet to swallow.

That first section is the foundation for the wider examination of ‘home’. The two sections speak to each other, as across a border, about borders and what a home might be. For Lotfi it’s Scotland, but touched with a nervousness, with a fear that it might not last. ‘Citizen’ describes a dream where her name is checked on a list, and rejected:

In my dream, I push through the exit and walk home in rain to a house that isn’t mine, in a country that isn’t mine.

Absence, a lack of permanence, haunts these poems. ‘Number 9 Cullipool’ shows a lobster fisherman and the detail of his work.There’s a ritual to his routines whether daily or seasonal, even in his morning words of farewell to his wife as he leaves: “If you find yourself in the sea, / too much has already gone wrong.” The words recall ‘The Last Thing’ from the first section, in which a mother tells her son to put his coat on, (every mother’s eternal reminder):

The morning he leaves, she pushes it into his bag like a relic, listing the reasons he’ll need the weight, winter is coming. It’s the last thing he loses. When all the bags are gone and the men chest-deep in water hauling the boat to land, he keeps his shoes for shore, flings the coat overboard.

‘The Last Keeper’ envisages the last night of the Barns Ness Lighthouse before it was automated in 1986, and the keeper who “polishes the silver and trims / the wick for old times’ sake, wanting things // to be right and true, though no one else will know.” Personal departure sits underneath this apparently non-personal poem. ‘Moving’ is directly personal, but slant: in leaving a rented house she wants to leave a light on “not for us – / […] but for our absence”. The poems are circling around what home might be and where it might be found.

It’s this depth that I’ve found most satisfying in Lotfi’s work, the way her past is inescapable and shapes her thinking about the present

Does the final poem bring resolution? It ends with a question, as though even a (possibly) positive statement has a question within it, worrying at the surface from underneath. It’s this depth that I’ve found most satisfying in Lotfi’s work, the way her past is inescapable and shapes her thinking about the present. ‘The Hebridean Crab Apple’ has an explanatory subtitle: “mysterious lonely apple tree on uninhabited Hebridean island baffles scientists”, and opens:

This, I understand: the instinct to cling, at any cost, to the place you are rooted, to see another season through, though the others seed elsewhere.

The poem concludes:

And what is home if not the choice – over and over again – to stay?

Thrown back to the reader, this acts as an invitation to return to the first poem (‘Refuge’) and re-read the collection. However, Lotfi’s work is too nuanced, too reflective, to insist on a single answer. She isn’t the right person to ask because she knows how complicated the whole question is which may, paradoxically, make her exactly the right person to ask. These poems are her answer. They speak directly to the reader, which is what makes them so memorable. And they are relevant: just look at the news.

D. A. Prince lives in Leicestershire and London. Her second collection, Common Ground (HappenStance, 2014), won the East Midlands Book Award 2015. Her most recent collection, The Bigger Picture (also from HappenStance) was published in 2022.

Marjorie Lotfi is a poet, performer and creative writing facilitator living in Scotland. Born in New Orleans to an Iranian father and American mother, Lotfi moved with her family to Iran as an infant. They lived in Tehran until returning to the USA at the onset of the Iranian revolution, living in Ohio and California before settling in Maryland. After university, Lotfi attended law school, going on to practice corporate law in New York. She moved to London in 1999, and Edinburgh in 2005. Her pamphlet, Refuge, was published by Tapsalteerie in 2018. The Wrong Person to Ask (Bloodaxe, 2023) won the 2024 Forward Prize for Best First Collection.

As well as browsing our Substack, it’s worth visiting The Friday Poem website where you can browse our Archive of more than 700 posts dating back to early 2021. If you like D. A. Prince’s writing, try her reviews of Broadlands by Matt Howard (Bloodaxe, 2024), Taking Liberties by Leontia Flynn (Cape, 2024), or Before We Go Any Further by Tristram Fane Saunders (Carcanet, 2023). If you want to know more about D. A. Prince’s poetry read Annie Fisher’s review of her third collection from HappenStance, The Bigger Picture.

Help support The Friday Poem – buy us a coffee to help us stay awake as we strive to bring poetic excellence to your inbox every Friday. If you can't afford to donate, no worries, we’re going to keep on doing it anyway! Big thanks for everything, you lovely poetry peeps.

What a fantastic poem. It sent me into shivers.

Thanks,

Hiram Larew

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIS_9MKye84