The Friday Poem on 24/01/2025

Do you have a pet poetry hate, something that has you reaching for the red pen, a word that you think should be barred from all use in poems? Here are three of ours.

Steven Lovatt on ‘heft’

As a verb meaning to move something, ‘heft’ is colloquial, fresh and unobjectionable, but as a noun, used as a synonym for ‘weight’, it’s indulgent, even pervy. If something in a poem has heft, as opposed to weight or mass, then you’re supposed to indulge the hefter in his or her pious treatment of a special object, like your Old Dad’s spade angled out of the rich, gently steaming loam etc., with the poem zoomed in on his careworn hands warming the grain of the wooden handle. Sickening.

Objects are difficult to write poems about – much more difficult than experiences, ideas and states – and until a few decades ago anglophone poetry tended to avoid direct confrontation with them. Now you can scarcely read a poem that doesn’t strain for evocative juxtapositions of objects. There’s the safely unpolitical orientalism-by proxy type (saffron, cowries, alabaster), the industrial-heritage type (tinplate, bitumen, Betjeman) and the ‘edgy’ type (spandex, nettles & piss). I know that much of this is fed by pathos, and that the liquefactions of value required by consumer capitalism produce a genuine homesickness for objects. But caressing your pre-digital detritus in tender wonderment is not the answer, unless the question is ‘how can I ruin the experience of reading my poem by reverently signposting the affective bit?’

‘Heft’ isn’t solely responsible for this, sure, but it’s very often present at the scene of the crime. The heft of the ivory cigar box, grandma’s paperweights and great-uncle’s crown green bowls; the heft of anything from fifty to one hundred years old that you want to upgrade to timeless, like a saint’s shinbone; anything aureoled, sunwarmed and motey. And if you really want to peddle this meaningful object like a pro, if you want the best-situated stall just next to the shrine restrooms at Lourdes and Knock, with a shaft of light anglepoised at all times onto the expectant brocade, then you’ll not even dare breathe the name of the sacred thing. You’ll just extoll its smell, its texture, then you’ll lift it gently and whisper ‘The heft of it!’

Poets, stop! Stop fondling stuff. It makes your poem look mawkish and me feel less like a reader than a voyeur. Honestly, just pack it in.

Jane Routh on ‘hunker’

To travel west from here I have to cross the Lune. If I use winding local roads, Loyne Bridge is the nearest crossing, an elegant seventeenth century single-lane sweep of stone across four arches with refuges above its central cutwaters. It had replaced a medieval bridge, which in turn had replaced a ford. Once, it must have been a busy route: the ridge along the eastern bank is topped with a defensive motte and bailey. And at the edge of the bailey is a WWII pill box.

This is what I see every time I come across the word hunker in a poem: I immediately visualise someone crouched down inside that bunker above Loyne Bridge because the sounds (and activities) of those two words correspond so closely. It’s an unfortunate image since so many poetic hunkers happen in landscapes that aren’t in any way improved by images of Second World War slabs of concrete. But hunker’s what you do inside a bunker.

And hunkering happens far more often than is called for. Have you noticed that no one crouches these days? No one squats either, let alone hunches or stoops. Even children in their dens – surely places you should be able to rely on to hand on age-old traditions in whispered secrets – no longer huddle. No: hunker is the go-to word these days. Whether they kneel, perch, sit on their heels, sit cross-legged, recline or simply sprawl, poets hunker. We all now do that manly thing.

‘Manly’? First cousin to hunk, it’s a word which steps forward flexing its muscles, drawing attention to itself, declaiming itself to be strong, outdoorsy, determined, in charge. Its elbows stick out. It’s not a word that’s at all keen to fit in unobtrusively or help others along. It shouts about wanting to do more than “squat so the haunches nearly touch the heels” as the Shorter Oxford has it.

Resolving never to use the h-word myself put me in a tidy spot a couple of months ago while writing about an early memory of being with a group of men with shot guns who xxxxxxed down in a ditch, waiting for ducks to fly over as the light faded. As it happens, the bunker association would probably have fitted fine into that context. Such is my dislike of the h-word, I stuck to my prejudice and had the men settle themselves quietly into that ditch.

I’m attributing my dislike of hunker to its sounding like bunker but as I wade through the 732 pages of Don Paterson’s The Poem, I find I should have said that it is a phonestheme, which he defines as “a point of sound-sense coincidence” – that is, the very sound of the word itself carries a meaning. And “unk” words happen to be one of Don Paterson’s examples. All of them, he says, have “a sunken, heavy, concave ‘feel’ to them, even though most are etymologically unrelated”. (Let’s add in sunk, funk, junk, puncture, dunk and so on, and you’ll get the picture.) This is definitely not a feel-good word, either.

But in addition to people who xxxxxx in poems, I’ve also read poems in which grape vines do it. And in which wolves do it. Donald Hall even has houses do it (though maybe he gets away with the surprise of that). And as for Seamus Heaney – what about “all those // Hunkerings” in ‘Squarings’, or “the women after dark / hunkering there a moment before bedtime” in ‘Keeping Going’ , or “A lust that’s bred during the squawked attack / Freezes the eyes, contorts the bawling mouth // Of every sporty punter hunkered there” in his poem ‘On Hogarth’s engraving, “Pit Tickets for the Royal Sport” ’.

Though there is one I can take – perhaps because in his poem ‘In Memorium Francis Ledwidge’ my bunker image fits or, more likely, because the word is so powerfully disrupted both by the adjective that precedes it and by the noun it qualifies:

The bronze soldier hitches a bronze cape

That crumples stiffly in imagined wind

No matter how the real winds buff and sweep

His sudden hunkering run, forever cranedOver Flanders.

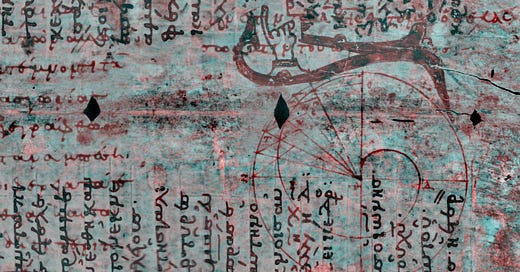

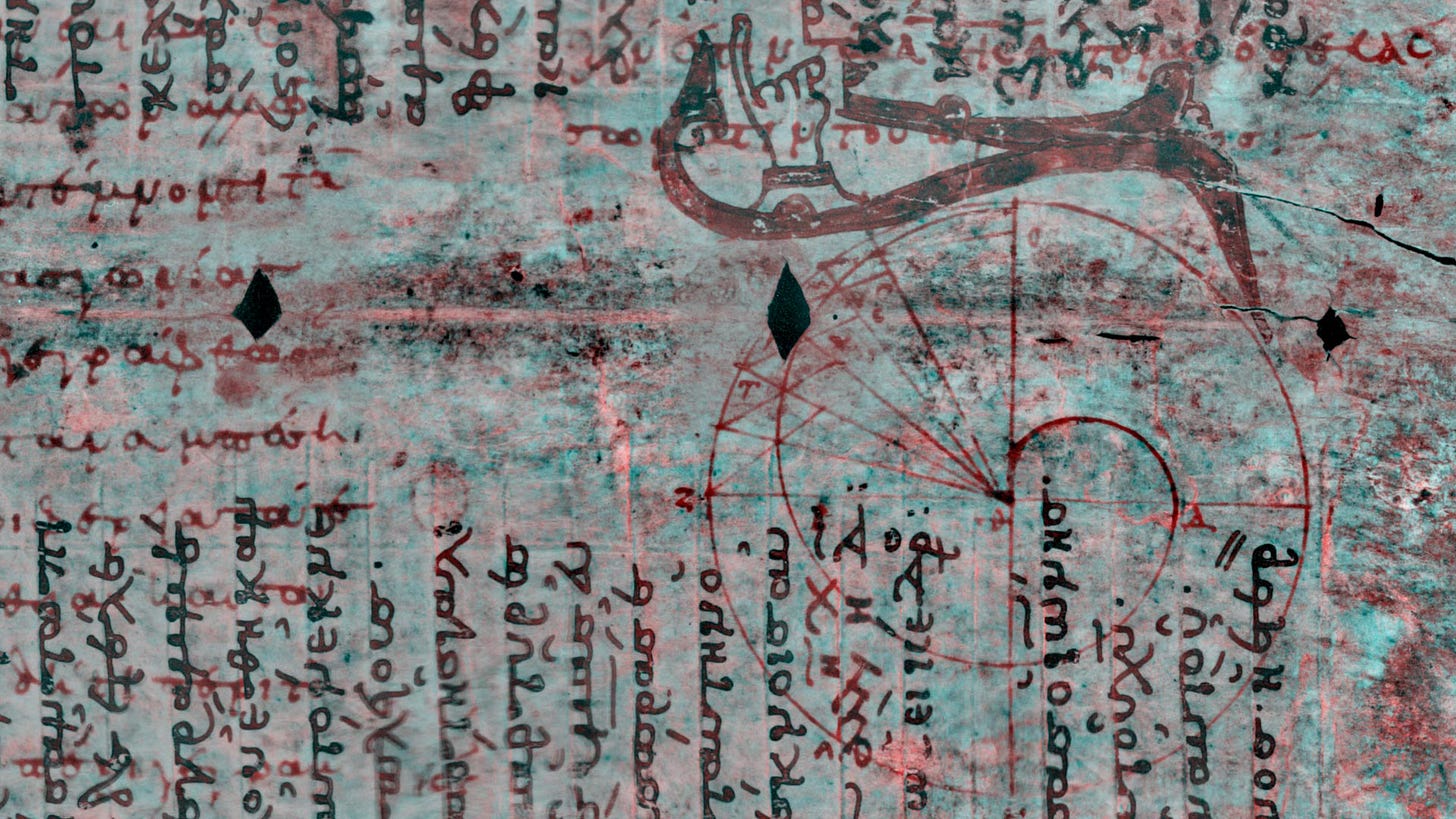

Chris Edgoose on ‘palimpsest’

/ˈpalɪm(p)sɛst/, noun, a manuscript or piece of writing material on which earlier writing has been rubbed out to make room for new writing, or where new writing has been superimposed on old

A palimpsest is a ‘palaeographic object’ (I know that because I read this article). In the non-poetic world, you’re only going to need the word very occasionally and probably only then if you work with ancient manuscripts (I mean, there might be times; I remember once seeing an old pub name bleeding through a new one painted on the outside wall of the pub and I guess I could have pointed out to the person I was with that it was a palimpsest, but I’m not sure it would have improved the evening).

On the other hand, if you’re a poet who is looking to express figuratively a layering of meanings, one set of meanings poking through into another set – in other words, if you’re looking for a metaphor for Metaphor, then palimpsest is a useful word. In fact, it’s probably the perfect word. And it knows it, smiling out at you smugly from its nest of lesser words, dominating everything else in the line, the stanza, or even the whole poem, using up the oxygen of all other metaphors in its proximity the way a famous line in Shakespeare takes up disproportionate space in the scene where it appears. And ultimately that’s palimpsest’s downfall, it’s too good. It’s just too much of a gift to the poet. It feels like an almost lazy act to select this great, bloated sitting duck of a word; to be seduced by its perfectly literary, historical and academic credentials. Its metaphorical value so outweighs its practical value that it’s like a tool invented specifically for poetry; a gift handed down by the Muses themselves to help out the floundering mortal bard. It’s tempting to think that a word like palimpsest is too good not to use; but it’s not, it’s too ‘too-good-not-to-use’ to use.

And there’s the impressive nature of the word’s structure itself: it looks and perhaps sounds dactylic, but it’s more fruitfully approached as a poem in itself. That unusual (audacious even) central consonantal cluster mps dominates*, bisecting the micronarrative; a leafy opening trochee palim and knife-like closing syllable sest are beautifully balanced, the plain, almost damp, first two-thirds transformed into something majestic, mountainous, by the superlative ending: if it were an adjective it wouldn’t just be palimps, it would be the palimpsest. As we open the word up we find this surreal terrain compounded by its etymology, where digging down we find palin and psestos in its Greek roots, conjuring, of course, Monty Python and Italian sauces.

There are great humble words and great hubristic ones, and palimpsest falls in the latter category. It’s a self-satisfied word, plump with its own perfection; but for all its flourish and preen, there’s no hiding that behind the perfection lies not the lamp of inspiration or the Everest of metaphors (as I once thought), but pap, pimp, limp, lame, psst and pest.

Or am I being unfair?

*mps is not altogether uncommon, especially when counting endings of third-person verbs, but rarer in a central position in nouns, and phonologically for the cluster to be followed by /e/ is unique, I think.

Steven Lovatt is the author of Birdsong in a Time of Silence (Particular Books, 2021), shortlisted for the Richard Jefferies Prize. Over the last decade his reviews and critical articles on Welsh and European literature have been published in New Welsh Review, Planet, Critical Survey and the Literary Encyclopaedia. He teaches literature and creative writing at the University of Bristol, and copy-edits books on ethnography and philosophy from his home in Swansea.

Jane Routh has published four poetry collections and a prose book, Falling into Place (about rural north Lancashire) with Smith|Doorstop. Circumnavigation (2002) was shortlisted for the Forward prize for Best First Collection, Teach Yourself Mapmaking (2006) was a Poetry Book Society recommendation and she has won the Cardiff International and the Strokestown International Poetry Competitions. Listening to the Night was published by Smith|Doorstop in 2018. A pamphlet, After, was published by Wayleave Press in 2021. Her latest collection is The Luck (Smith|Doorstop, 2024).

Chris Edgoose is a poet and blogger at Wood Bee Poet. He lives near Cambridge in the UK, and has had work published in several magazines in print and online.

As well as browsing our Substack, it’s worth visiting The Friday Poem website where you can browse our Archive of more than 700 posts dating back to early 2021.

Help support The Friday Poem — buy us a coffee to help us stay awake as we strive to bring poetic excellence to your inbox every Friday. If you can't afford to donate, no worries, we’re going to keep on doing it anyway! Big thanks for everything, you lovely poetry peeps.

I don't dislike these 3 words, or indeed any word provided it's doing a good job. I particularly like the concluding lines from Seamus Heaneys "Clearances":

Deep-planted and long gone, my coeval

Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole,

Its heft and hush become a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence listened for.

On the other hand there is one word I dislike, mainly used outside poetry: amazing. It is a blanket word that smothers true evaluation, and is used lazily.

'curated'